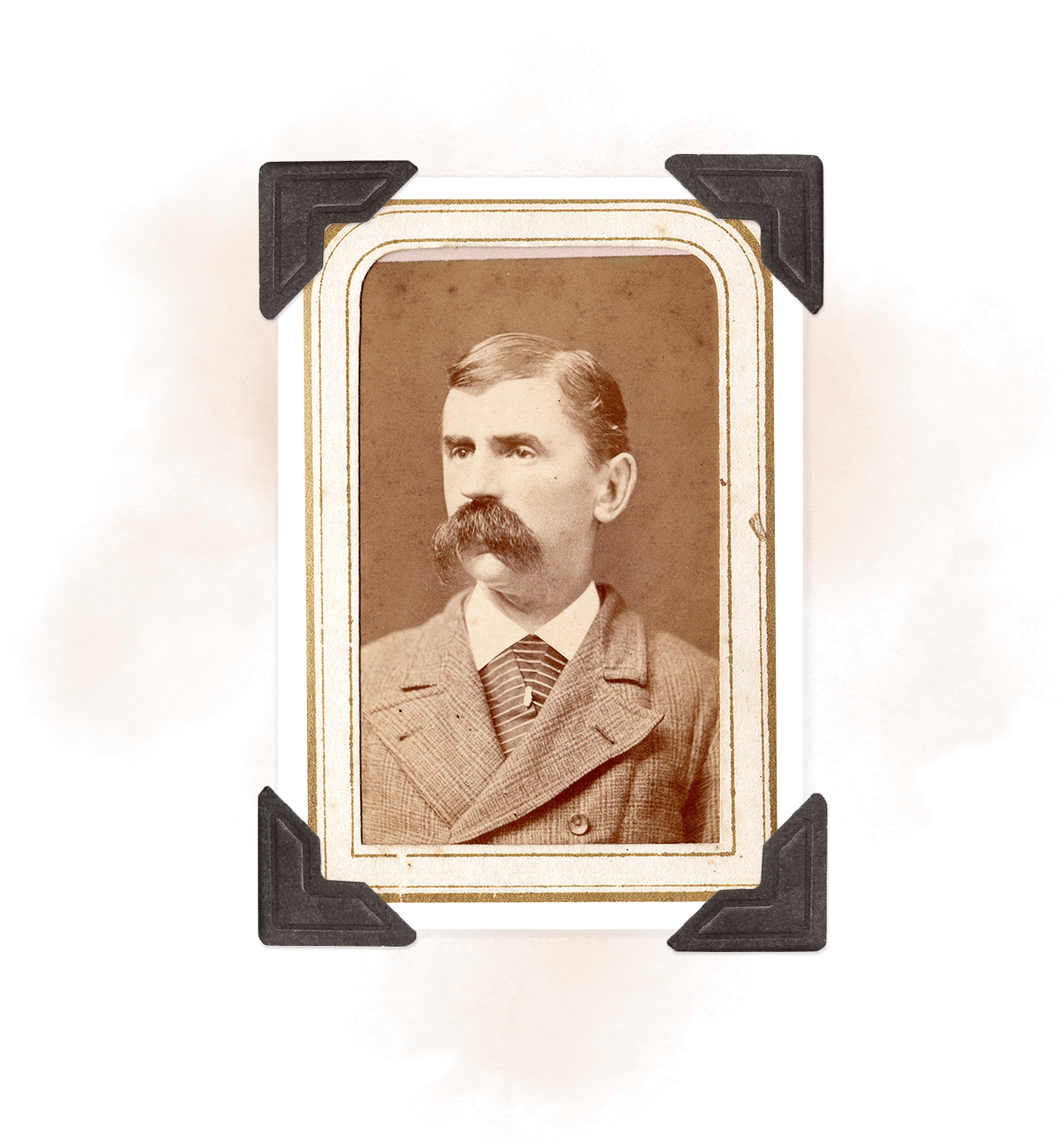

Hidden in a sycamore tree by the foothill road, ten year-old Leander was killing time watching for the afternoon stage. He spotted a rolling dust ball gathering size in the distance. Then came a rumbling in the earth, traveling faster than the coach itself. At last, with the rattling of the rig and a stream of hot words from the driver, the stagecoach pulled up—much to his surprise—right in the shade of Leander’s tree.

“You think I’m just your fartcatcher up here?” Cornelius Crookshank snapped a black leather whip over the backs of his team. “And you,” he singled out one buttermilk colored mare, “you useless hunk of horsemeat, I’ll whip you to a pudding!” The driver was too busy to notice the boy in the sycamore tree.

When the lead mare planted her feet, her partner-in-harness gave a gentle nudge of the nose. He understood. Quick as a flash flood in the desert, the mare bore down and delivered two legs, a rump, and a torso. Withers, head, and front legs followed—collapsed all together like a folding chair. The newborn horse was covered with thin mucus—like the clear snot leftover in your hand after a giant sneeze.

Nobody stood by to catch the foal.

“Hey!” Leander called out.

“Who said that?” the driver snarled.

Leander froze. In all his ten years, he had never heard anyone so downright mean.

Passengers grumbled inside the coach. The driver looked up at the overloaded baggage platform on top of the stage. He shook his head. No room up there; no room inside.

The man jumped down from his seat like a nimble predator, spit tobacco juice into the dirt road, and removed his hat to scratch his head. He poked his nose into the cabin and barked: “You people just sit tight!” Inside, the passengers stopped mumbling.

When Buttermilk tried to nuzzle her foal, the driver kicked her away. The gelding alongside the mare whinnied in protest, yanking his head up and down. The exhausted mother was taking long, deep breaths.

“We’re wasting time,” the driver said.

His shotgun rider got the message and hopped down from his high perch to help his boss drag the foal off to the side of the road and chuck it into a ditch.

Only minutes had gone by when the two Butterfield Stage men climbed back aboard. The shotgun rider put his weapon across his lap. The driver spat into the road again. He cracked the whip in the air, barely touching the animals this time. The four horses walked on. Trotted a little. Walked a little. The driver was quiet.

In seconds Leander understood if he didn’t act right now, the foal would die. With the stagecoach pulling away, he slid down from the sycamore tree. He would show Ernesto Trujillo—and the rest of the boys—he knew something about horses.

First, he took out a handkerchief and wiped the slimy film away from the foal’s eyes and nostrils. Then, opening its mouth to clear out the mucus, Leander reached in to scoop out anything blocking the airway. Just that little disturbance tickled the newborn horse into coughing.

“Good work, little pony,” the ten year-old pressed his cheek against the foal’s damp muzzle, feeling the warmth. “Keep breathing, little one. I’ll be right back.” Up and running across the soft earth furrows of the orchard, Leander McFarland headed home for help.

Robert McFarland was washing his hands at the pump in the barnyard, as he listened to his son describe the scene for him. “Fetch that old blanket in the rocker on the porch, son,” he said. “ You get going and I’ll meet you there.”

Leander snatched the blanket and raced back where the newborn lay helpless by the side of the road. McFarland was slower, taking time to hop over his furrows to save their shape. When he reached the pair, the boy had spread the soft wool covering over the foal, rubbing ever so gently to let the newborn know they were there to take care of it.

“It’s breathing, Papa.”

“Good. Now let’s try to keep it warm.”

Together they lifted the colt and tucked the blanket around it. “I’ve got her now, son,” Mr. McFarland promised. “Run ahead and tell your mother we have a visitor and we need some milk pronto.”

Mr. McFarland carried the blanket-wrapped orphan foal through the peach tree orchard, the rows of grape vines, past the barn and up to the house. On the pine floor near the fireplace, Leander was already putting together a pallet, a rough bed of soft rags and old blankets over straw. McFarland laid the little guest down with the greatest of care.

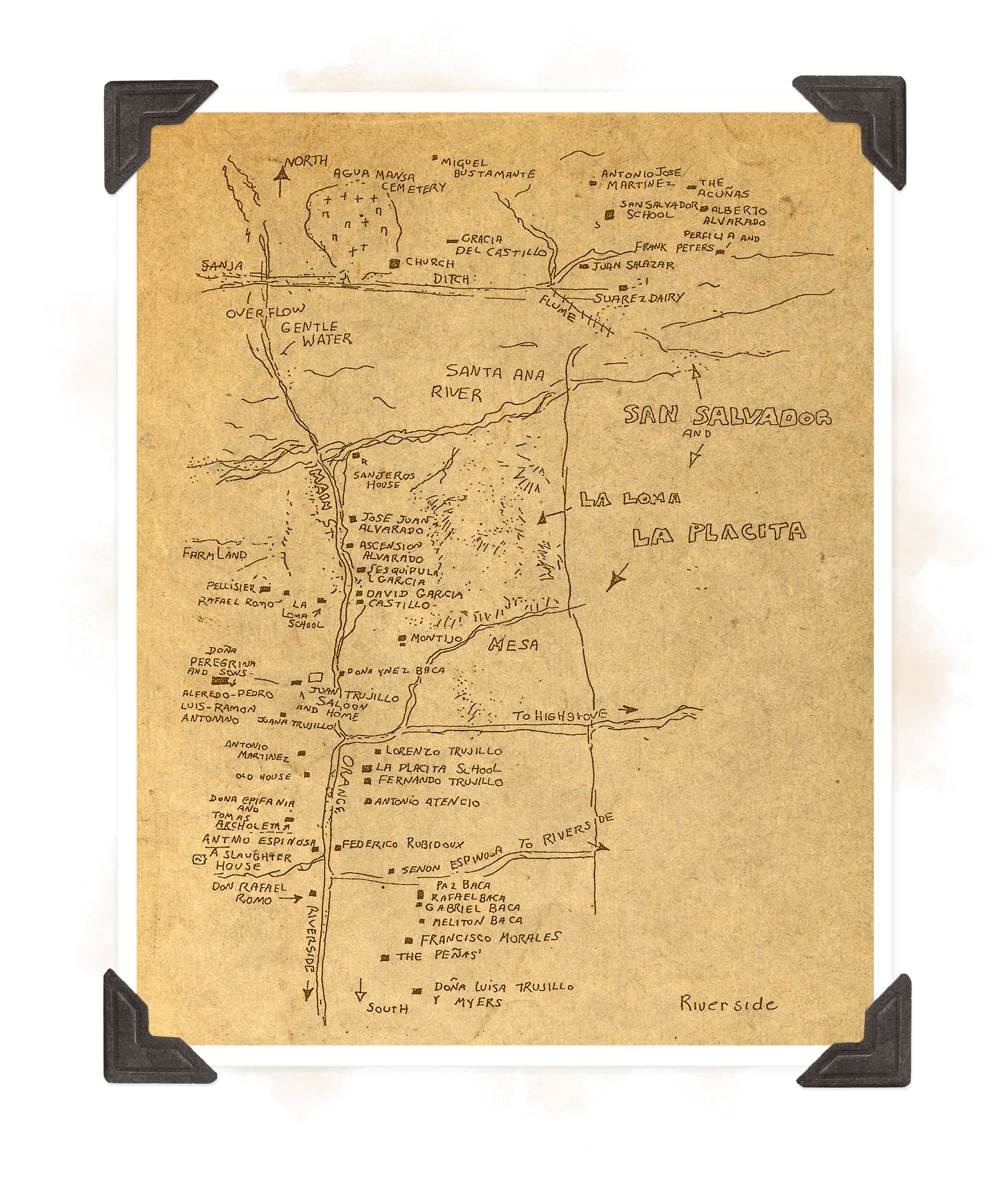

Rosetta Trujillo McFarland was waiting. She knelt down beside the baby horse and let it smell her hand. Then she dipped her fingers into a saucer of milk and moistened the filly’s nose and lips.

“This baby needs a ninny,” her husband said. “I’ll show you how my grandmother used to do this.” He found a clean wool sock, poured milk into it from a pitcher, then twisted the top and offered the dripping wet sock to the foal. The infant horse was interested, but she wasn’t sure about sucking on a sock.

“Maybe it’s just an Irish thing,” McFarland worried.

“It’s only cow’s milk,” Rosetta reminded her husband. Then she turned to Leander. “This baby needs goat’s milk. Hurry, hijo, find Corazón and bring her to me. And bring my milking stool.”

And so began the shouting back and forth between Robert and Rosetta McFarland over whether cow’s milk or goat’s milk was better for a newborn orphan horse. The parents were still arguing when Leander returned with Rosetta’s favorite brown and white goat Corazón, named for the white heart shape on her light brown forehead.